Text of and Correspondence with Prof. em. Günter Pichler, Primarius of the Alban Berg Quartet, Conductor, and Longtime Professor of Violin at Institute 5, now the Fritz Kreisler Institute at MDW

As part of my piano teaching at MDW, I frequently refer to recordings of the ABQ—Alban Berg Quartett—when appropriate. The ABQ was one of the world’s leading string quartets for decades, a fact well known to all connoisseurs of the genre and beyond, even though the quartet ceased its active career in 2008 after thirty-eight years. By that time, the ABQ had already long become a legend, as evidenced by countless recordings.

For example, in 2020, one could highlight their complete recordings of Ludwig van Beethoven’s string quartets—considered a reference recording (with the lineup: Günter Pichler, Gerhard Schulz, Thomas Kakuska, and Valentin Erben). In the same breath, one could mention their complete recordings of Franz Schubert’s quartets (including his string quintet), as well as the string quartets of Bartók, Mozart, Haydn, and many others.

For me, this ensemble was one of the great musical guiding influences during my studies, and it remains so to this day.

•On one hand, the string quartet repertoire, alongside orchestral literature, is central to a pianist’s repertoire studies. Engaging with Beethoven’s string quartets, for instance, is a natural complement to studying his piano sonatas: How does a four-part texture sound? How does the composer develop his ideas for four string instruments? And so on.

•On the other hand, the ABQ’s regular subscription concerts at the Wiener Konzerthaus over the decades were consistently highlights of sensitive and transparent interpretation, instrumental precision, highly expressive beauty of sound, and profound musical insight. Many other aspects could be mentioned here.

During my training at MDW, I had the opportunity to make chamber music and explore the corresponding repertoire under the supervision of Prof. Günter Pichler, the founder and primarius of the ABQ, together with students from his class—among them the wonderful violinists Tanja Becker-Benderand Bojidara Kouzmanova,. This was an immensely enriching experience.

In this context, the correspondence in question took place in 1998. With Günter Pichler’s consent, I am publishing it here.

His presentation of an “approach to interpretation” remains just as relevant to me today—perhaps even more so than at the time. With the experience I have since gained, I can now better grasp the depth of his insights, how profoundly he engaged with the musical material, and how crucial the interpretative aspects he addressed truly are. His approach to interpretation was deeply intertwined with his decades of experience performing at the highest international level: the seemingly effortless, spontaneous music-making, while maintaining absolute clarity and precision in the work’s complex structure, was one of the many defining and remarkable constants in the ABQ’s performances.

The correspondence includes Günter Pichler’s text from January 4, 1998, and my response from January 10, 1998.

In the following the typed text with the handwritten annotations incorporated in italics at the appropriate places in the text (please see original fax pages enclosed in the end).

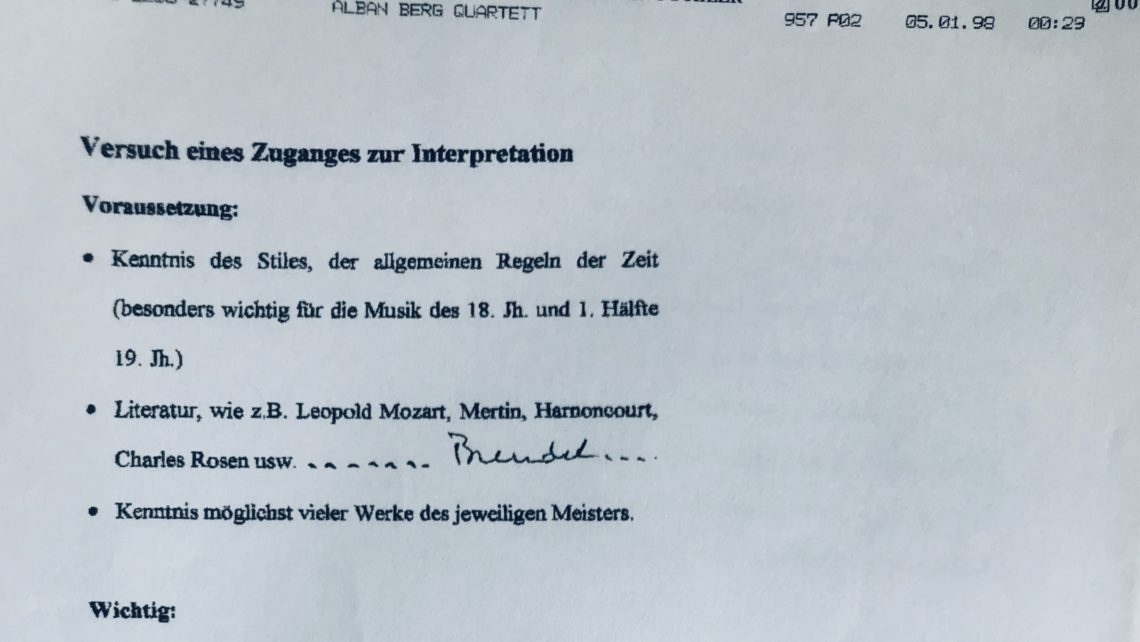

“Attempt at an Approach to Interpretation

Prerequisites:

•Knowledge of style and general rules of the period (especially important for 18th-century music and the first half of the 19th century).

•Literature such as Leopold Mozart, Mertin, Harnoncourt, Charles Rosen, Brendel, etc.

•Familiarity with as many works as possible by the respective composer.

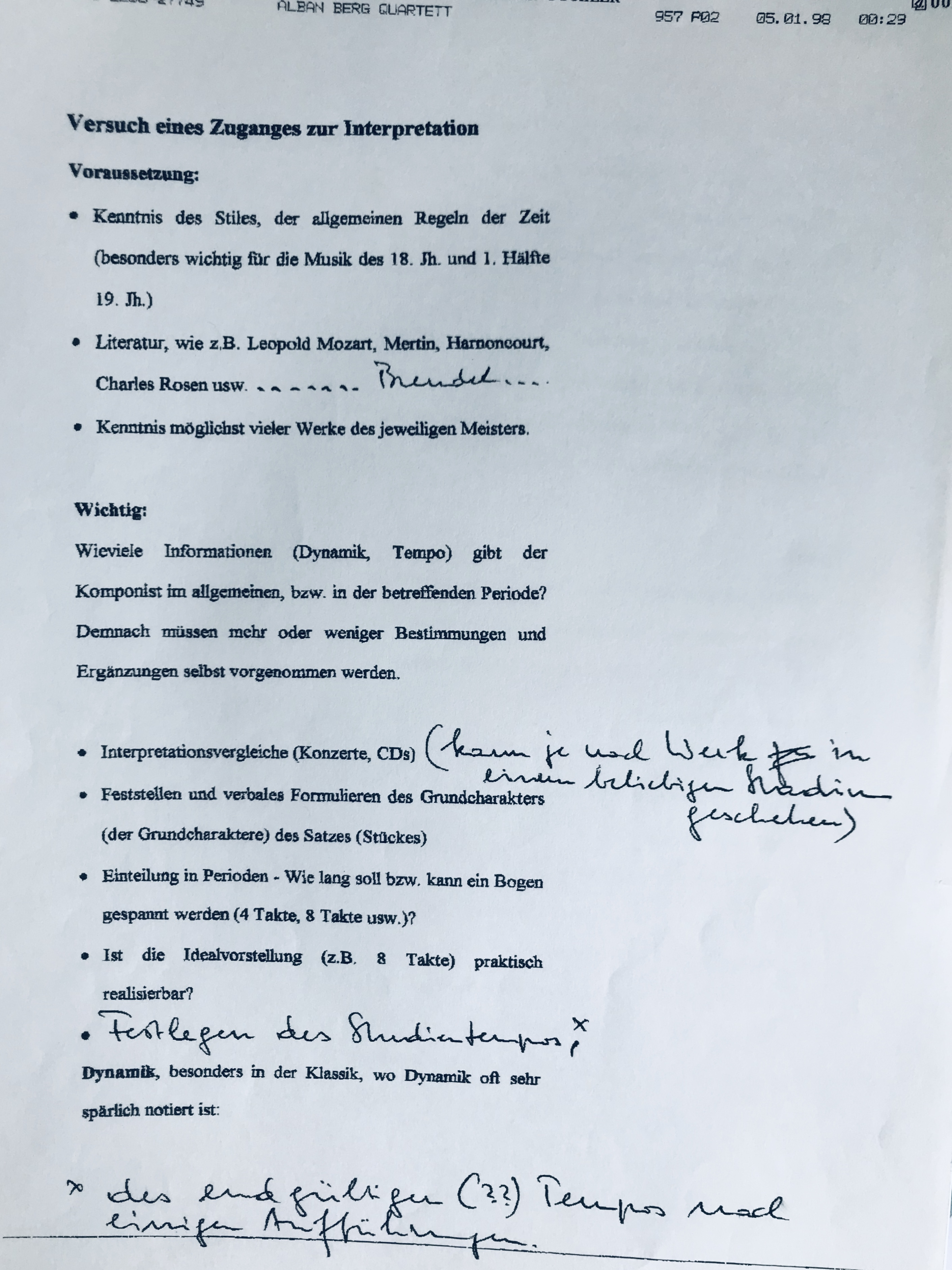

Important Considerations:

•How much information (dynamics, tempo) does the composer generally provide, particularly in the relevant period? Accordingly, more or fewer additions and adjustments must be made by the performer.

•Comparisons of interpretations (concerts, CDs) – this can be done at any stage, depending on the work.

•Identifying and verbally articulating the fundamental character(s) of the movement or piece.

•Structuring the phrasing – how long should or can a phrase be sustained (4 bars, 8 bars, etc.)? Is the ideal phrasing (e.g., 8 bars) practically realizable?

•Determining the practice tempo and the final (??) tempo after several performances.

Dynamics (especially in Classical music, where dynamics are often sparsely notated):

•Establishing focal points within a phrase.

•Adding missing dynamics (especially crescendo, diminuendo).

•Avoiding flat dynamics (which rarely occur in Viennese Classicism/Romanticism).

•For folk-like melodies, such as the final movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K. 595, using a “floating” dynamic—i.e., dynamic changes that are not consciously perceived by the listener.

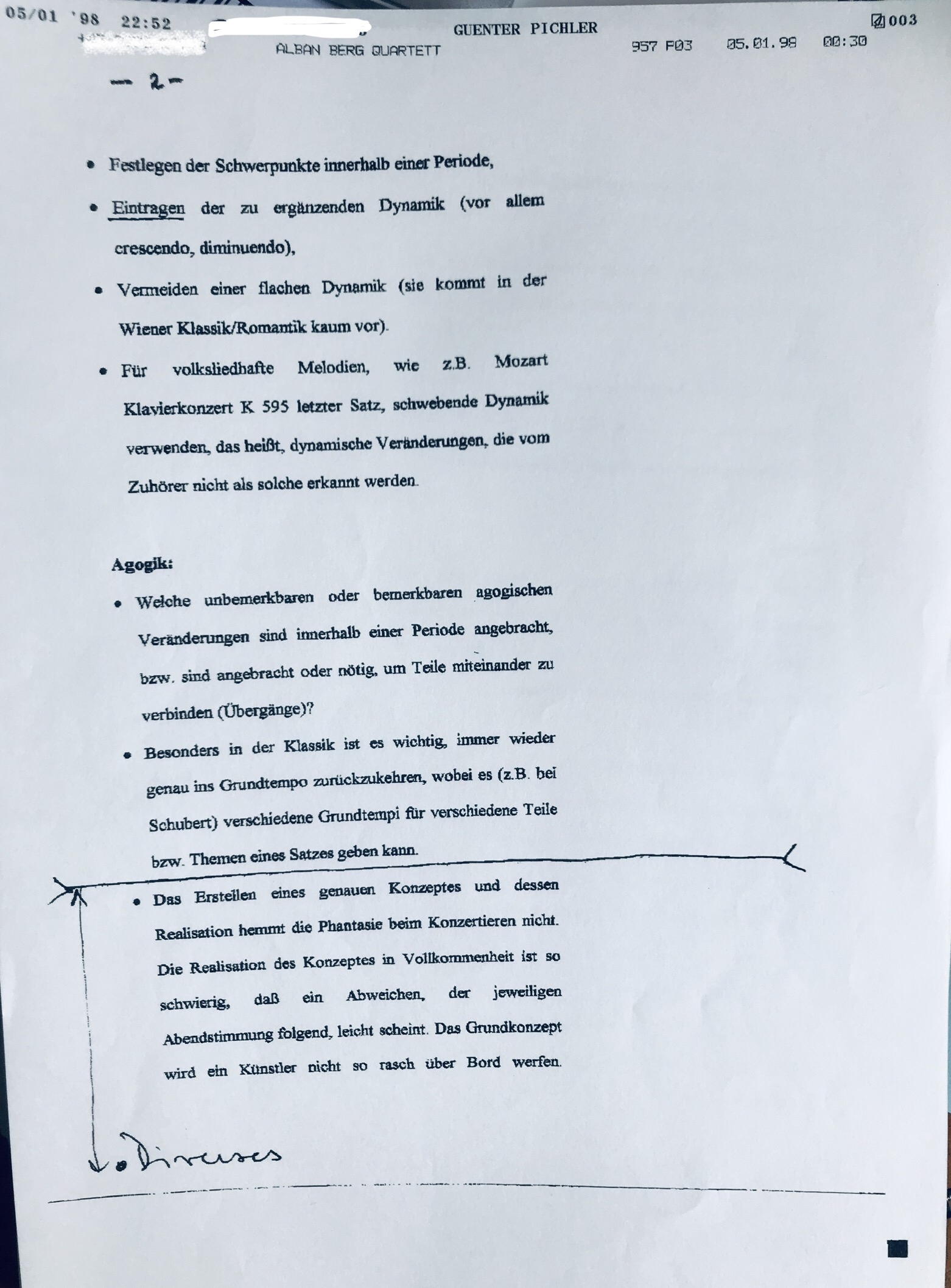

Agogics:

•What subtle or noticeable agogic variations are appropriate within a phrase? Are they necessary to connect sections (transitions)?

•Especially in Classical music, it is crucial to return precisely to the basic tempo, while acknowledging that composers like Schubert may use different basic tempi for different sections or themes within a movement.

Additional Considerations:

•Creating a precise concept and realizing it in performance does not hinder spontaneity in concerts. Executing the concept perfectly is so challenging that slight deviations based on the atmosphere of the moment feel natural. A true artist will not easily discard their fundamental interpretative framework. Spontaneous variations occur more in details, particularly in lyrical and Romantic movements.

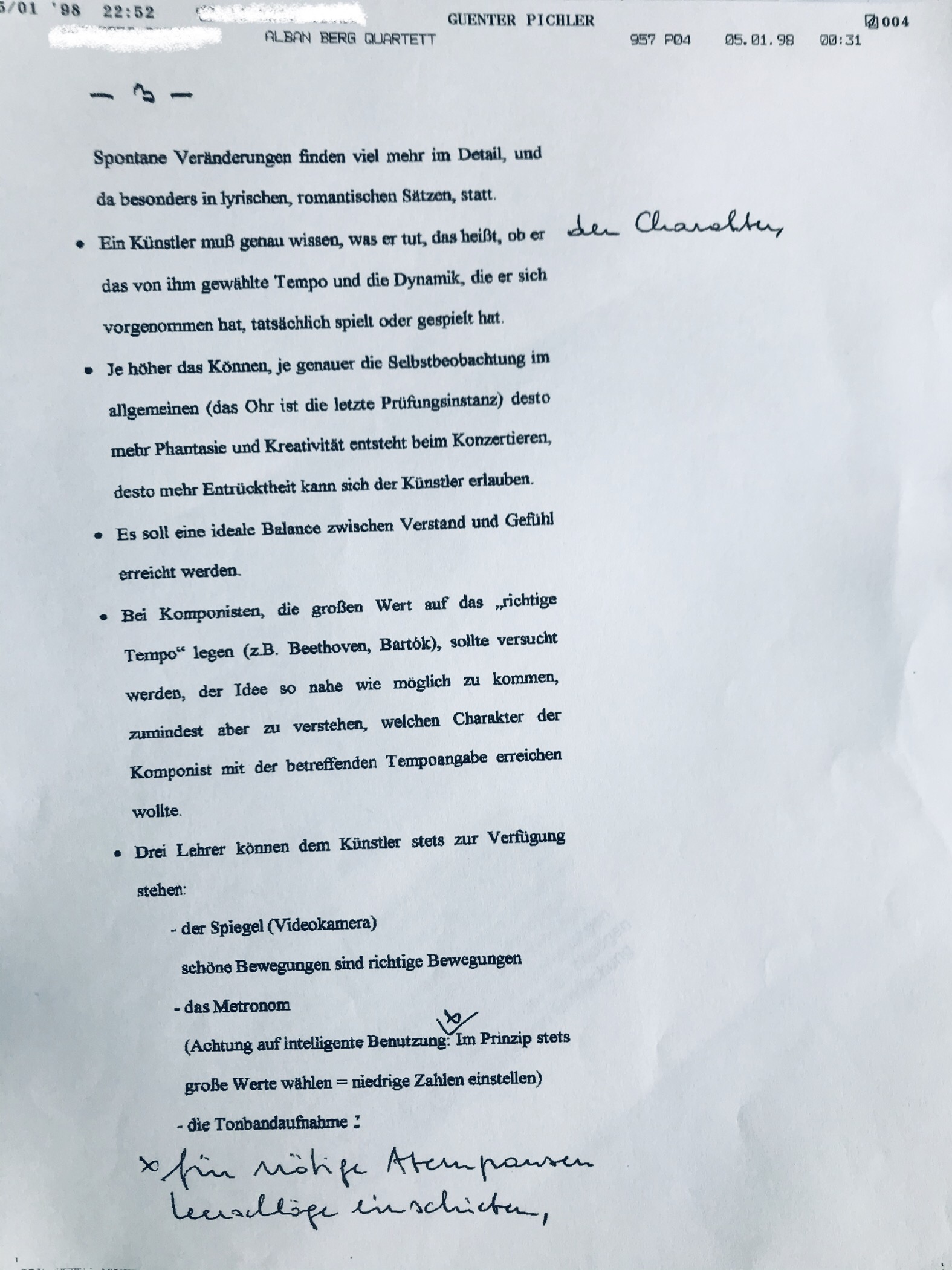

•An artist must be fully aware of their choices—whether they are truly executing the intended character, tempo, and dynamics as planned.

•The greater the skill and self-awareness (the ear being the final judge), the more creativity and spontaneity emerge in performance, allowing the artist to achieve a state of artistic transcendence.

•There should be an ideal balance between intellect and emotion.

•For composers who placed great importance on “correct tempo” (e.g., Beethoven, Bartók), one should strive to get as close as possible to their intended idea—or at least understand the character they aimed to achieve with their tempo markings.

Three essential “teachers” always available to the artist:

•The mirror (or video camera): Beautiful movements are correct movements.

•The metronome: Use intelligently—insert empty beats for necessary breathing pauses, and generally choose large note values (i.e., set lower numbers).

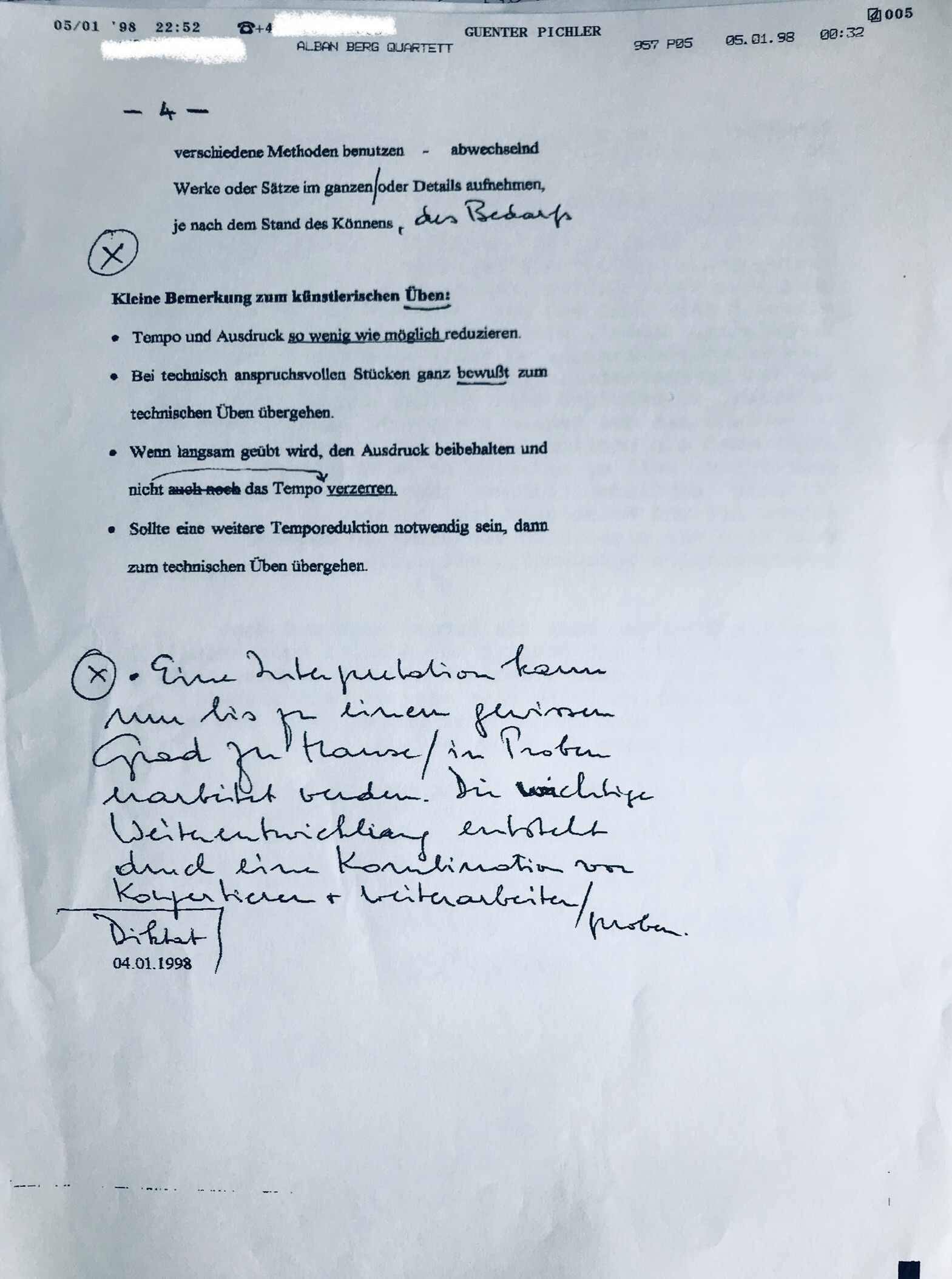

•Audio recordings: Use various methods—alternate between recording entire works/movements and specific details, depending on skill level and need.

An interpretation can only be developed to a certain extent at home or in rehearsals. True artistic growth occurs through the combination of performing in concerts and continued practice.

A small note on artistic practice:

•Reduce tempo and expression as little as possible.

•For technically demanding pieces, consciously switch to technical practice.

•When practicing slowly, maintain expressiveness and avoid distorting the tempo.

•If further tempo reduction is necessary, shift focus to technical practice.

Dictated on January 4, 1998″

© Günter Pichler, 1998

My response from January 10, 1998:

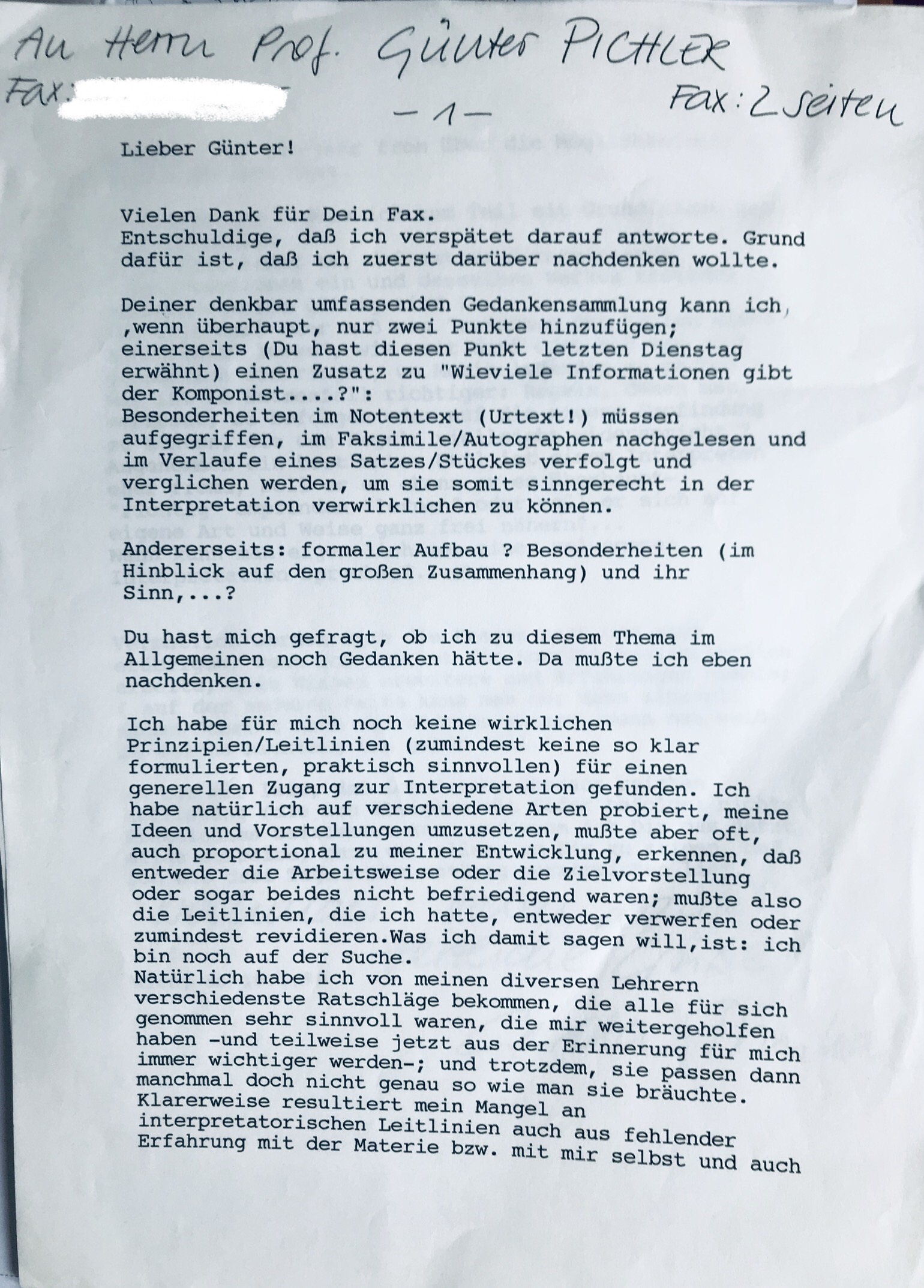

“Dear Günter,

Thank you very much for your fax.

Apologies for my delayed response—I wanted to take some time to think about it first.

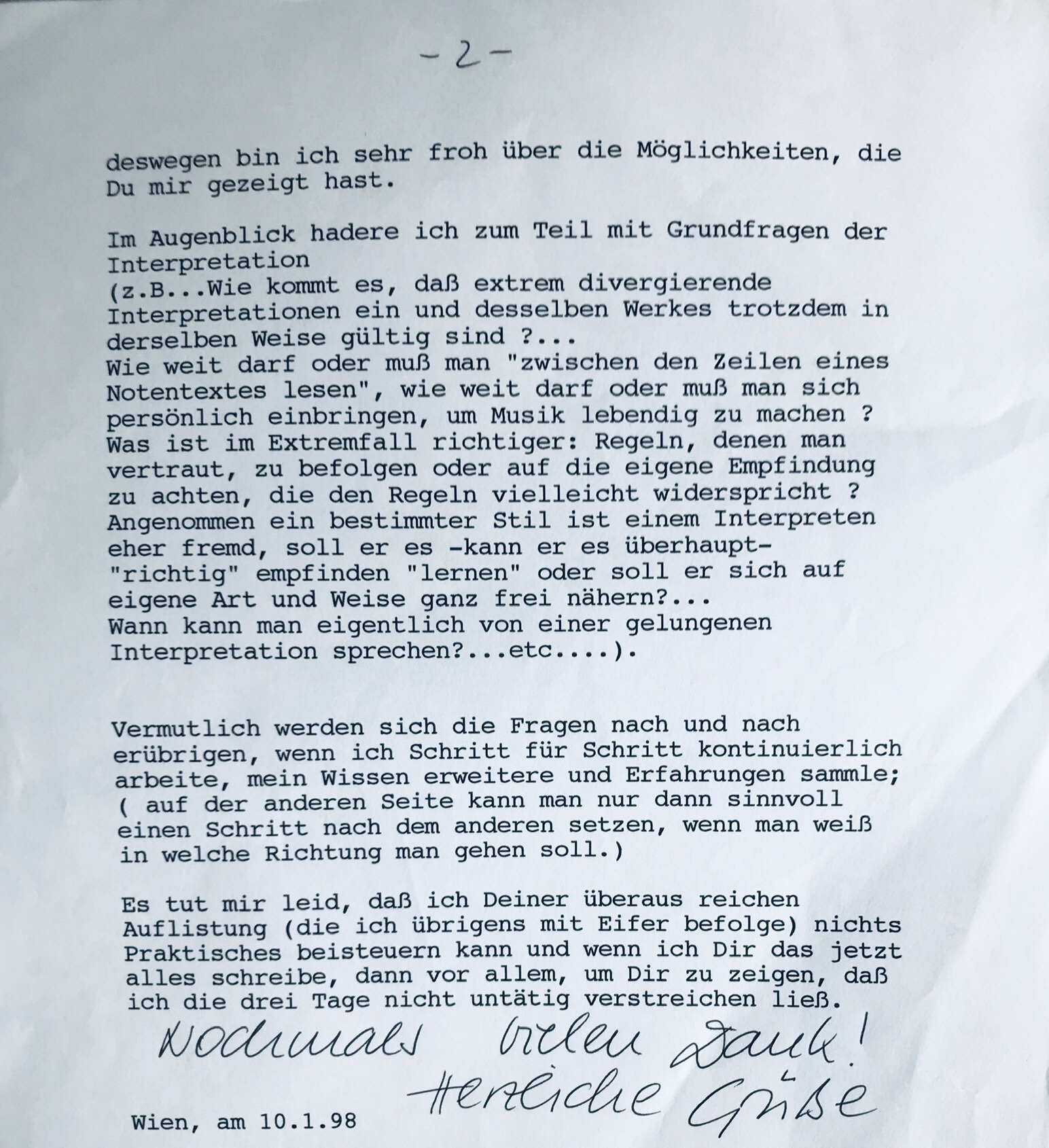

To your remarkably comprehensive collection of thoughts, I can only add, if anything, two points. One of them (which you mentioned last Tuesday) is an addition to your question: “How much information does the composer provide?”

Specific notational details (Urtext!) must be observed, checked against facsimiles/autographs, and tracked throughout a movement or piece to ensure their meaningful realization in interpretation.

The other point concerns formal structure: What are the structural particularities (in terms of the broader context), and what is their significance?

You asked me whether I had any general thoughts on this topic. That’s what I needed to reflect on.

I have yet to find clear, practically useful principles or guidelines for a general approach to interpretation. Of course, I have experimented with various ways to implement my ideas and visions, but I have often realized—proportionally to my own development—that either the working method or the goal (or sometimes both) were unsatisfactory. As a result, I have had to either discard or at least revise my interpretative framework. What I mean is: I am still searching.

Naturally, I have received countless valuable and insightful suggestions from my various teachers—many of which have been extremely helpful and, in some cases, are becoming even more significant to me in hindsight. And yet, they don’t always fit exactly as one might need them to.

It is clear that my lack of established interpretative guidelines is partly due to insufficient experience with both the repertoire and myself. That’s why I am particularly grateful for the opportunities you have provided me.

At the moment, I find myself struggling with fundamental questions of interpretation. For example:

•How is it that radically different interpretations of the same work can still be equally valid?

•How much should one “read between the lines” of a score? How much personal input is necessary to bring music to life?

•In extreme cases, what is more “correct”—following established interpretative rules or trusting one’s own instinct, even if it contradicts those rules?

•If a particular style feels foreign to a performer, should they—can they—learn to “authentically” feel it? Or should they approach it in their own way, freely?

•When can one truly consider an interpretation successful?

I suspect that many of these questions will gradually resolve themselves as I continue to work step by step, expand my knowledge, and gain experience. On the other hand, one can only take meaningful steps forward if one knows the direction in which to proceed.

I regret that I cannot contribute anything practical to your incredibly rich list (which I am eagerly following). The reason I am writing all this is simply to show you that I did not let these three days pass idly.

Once again, many thanks!

Warm regards,

Vienna, January 10, 1998″

© Gerda Struhal, 1998